In this article from 2014 John Miles shared some recollections and updates from an interesting period at Lotus’s engineering, automotive and motorsports operations.

It was 1983. Colin Chapman had died the year before, weighed down by the Delorean affair, the unfairly banned twin-chassis Lotus 88, and declining car production. His commitment to engineers Peter Wright and Dave Williams’ to fund a fully Active Suspension research vehicle remained, and there was also the embryo Vehicle Engineering section with chassis development at its forefront: a team of three working under Roger Becker, that was soon to quintuple in size.

The Lotus Sunbeam (winner of the 1981 World Rally Championship), suspension revisions on the Supra, and a driver training contract with Toyota had been completed. A big tuning job on a V6 GM Cavalier was next, and – heresy – we were looking at front-wheel drive for the new Elan! We were having dinner during winter evaluation of FWD versus RWD Corollas (FWD outperformed on every test) when into the hotel restaurant walked Tony Shute, then head of the tyre test department at Goodyear (GITC) in Luxembourg, to announce that GM had bought Lotus from the caretaker shareholders: Toyota, Amex, and BCA (British Car Auctions). Consternation reigned, yet fear was not warranted, as GM’s ownership turned out to be a golden period for the company.

Active Suspension was initially conceived for F1 at a time when skirted ground effect downforce was so powerful that F1 cars had to be human body breakingly stiff to keep them off the ground. With Active Suspension the car could have a relatively soft setup, with the actuators, which synthesised spring behaviour, extending to programmed positions to compensate for download. Soft meant grip, resulting in 2 GP wins for Ayrton Senna in the Lotus Renault Turbo 97T.

With engineer Mike Kimberley continuing as CEO, and Peter Wright as a technical guru switching between Team Lotus and Lotus Cars, there was a real engineering feel about the place. Major manufacturers – GM, Toyota, Saab, Volvo and the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) – were buying Active Suspension research vehicles as fast as Lotus could make them, and at last the Peter Stevens’ styling for the FWD Elan was signed off – having easily withstood some horrid competition from GM and Guigario.

Things were humming along but a certain over confidence existed. Active Suspension was brilliant as a race car system and as a research tool for road cars, even if it was super-sensitive to set up, and difficult to isolate from extraneous disturbances that would cause the whole system to become unstable. There was even a moment when Active Suspension looked like it was going to take over in the world of luxury vehicles – though levelling systems eventually did – rendering the normal suspension development that Lotus was so good at to the history books.

Unfortunately the boffins soon found out that the pump noise, actuator friction, and other problems associated with the Active Suspension’s 2,500psi hydraulics were insolvable , as were the problems caused by driving actuators of immense authority through rubber mountings – not to mention the system’s cost and potentially dangerous instability state. At the launch of the Active Esprit research vehicle I was hauled into the late Tony Rudd’s office to be told that “you can drive over a brick at 100mph and not feel a thing”. Err… I don’t think so, but never mind.

Among other achievements, Lotus Active did help get Thrust SSC through the Sound Barrier, and it certainly worked in various forms in Formula 1, as we proved at the revitalised Team Lotus in 1993. As far as I know the Lotus high-bandwidth system was unique in being able to simultaneously separate all body modes, allowing any combination of any body mode and damping, and only needing Active racks at either end to add in active four-wheel steer, as we tested in the four-wheel-drive Metro 6R4 V6-engined SID dynamics research car.

When I first re-joined Lotus in 1984, the passive group also had a wake-up call because the concept of the kinematic or compliance toe-out front-axle steer being necessary for straight-line stability was unheard of by me, or anybody else at Lotus. In fact Chapman’s race car bump-steer set up heritage was firmly in place and concentrated on eliminating any steer effects.

Yet at least 10 years earlier, GM, VW and others knew all about the importance of compliance and kinematic-steer effects, especially for cars with laterally weak twist-beam rear axles. As Peter Wright used to say, “tyres don’t know what they are attached to the car by, they only respond to vertical load, slip angle, and camber”. And as tyres were getting more responsive day by day, understanding and controlling small steer effects was becoming critical.

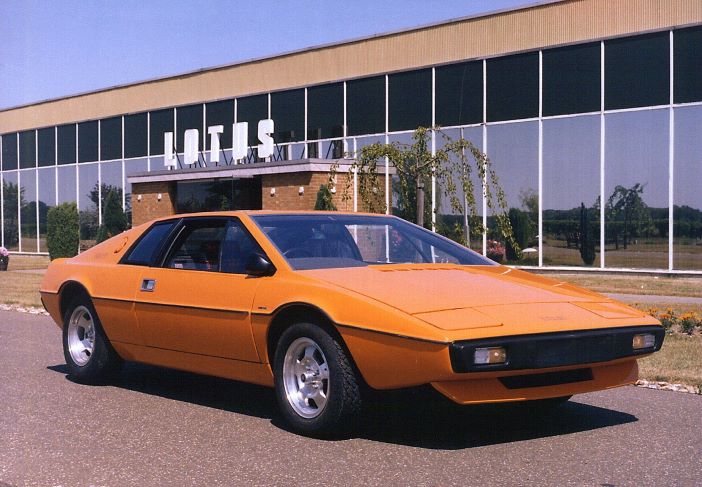

Rumblings about a replacement Esprit were always present, a car that by now had been transformed from the original version by three things. Chapman’s original rear-drive shaft as the top link concept resulted in having to have extra-stiff gearbox mounts to take the cornering loads. Awful NVH and indifferent handling resulted.

Chapman’s complaints about the humming roughness in the cabin could be easily answered with the inclusion of a top suspension link, a plunging driveshaft, and soft gearbox mounts, yet perversely forbade chief chassis designer Ken Heap from executing this setup. Chapman went on holiday with the instruction to fix the car by the time he returned “and I don’t care how you do it”. Two weeks later he drove a transformed car and asked what had been done.

“You told us to fix the NVH, or else, so we fitted a top link!” said Becker. Not long after came the transformational 260bhp Turbo version of Lotus’ 2.2-litre slant four, and then Peter Steven’s styling update, which looks good even today. As Esprits go, the Sport 300 is the best in terms of structural feel and grip, but award for the best power steering ever must go to the less focused S4S version.

Vehicle engineering was booming and, contrary to some expectations, the passive chassis group was expanding fast with contract work for GM, Rolls-Royce, and even Ford. The FWD Elan was now in production (painfully), but one sensed that GM was getting tired of its plaything against the backdrop of a worsening US economy. But still the place was humming for a bit longer, especially on the engineering side, with innovations such as noise synthesis, an F1 engine for Toyota, and lots of powertrain design and development work. There was also a re-born Team Lotus with Peter Wright back as team leader with the upgraded Cosworth HB-engined 102 (Herbert/Hackinnen) plus new type 107 and 107B Active in the hands of Herbert/Zanardi.

There was also the twin-turbo 3-litre Lotus Carlton/Omega. The car could have been average, especially as it was the last GM car with a steering box rather than rack and pinion. However, thanks to the correct tyre balance, and a small counter-intuitive 15mm height modification to one end of the standard Omega’s rear-steer link, which moved the rear suspension from generating kinematic understeer to slight toe-out steer (a nod to Magnus Roland), plus some brilliant damping work from Becker, the result was a sensationally refined 170mph express. Although there were places on the Autobahn where the Lotus Carlton couldn’t make it between fuel stations if you drove it hard!

All was about to change. The FWD Elan was not seen as a real Lotus and didn’t make money, whereas the Mazda MX5 did. By 1993 the US economy was not going so well and GM obviously wanted out, surprising us all by selling to a newly revived Bugatti – in effect one person, the rather charismatic Romano Artioli, who was usually shadowed by his flame-haired PA, Karen Angus.

Mike Kimberly had departed and the best one can say about the next three years was that the Elise got designed and put into production for peanuts by today’s standards, and the series 2 Elan got made thanks to GM donating the remaining stock of around 650 Elan Isuzu 1.6 turbo engines as part of the deal. We had already shown how an Esprit could feel better simply by making a five-fold increase in torsional stiffness, just to meet the best current standards of the day, and we were to prove later that it was a real GT2 competitor.

In production race trim the 300bhp Esprit Turbo was proving to be the best handing mid-engined car of the period, supported by a race programme in the US for the SCCA World Challenge, and then the IMSA Supercar series over four seasons starting in 1990, with Doc Bundy winning the IMSA Series in 1992, with a second overall the year after.

I had tried to put the case for building up the Esprit brand image, just as Porsche had done with the 911, with gradual updates keeping the classic north/south engine layout with its ideal 45/55 weight distribution. There was some agreement, but all the Lotus management could talk about was the cost of a gearbox to replace the time-expired Citroen unit.

But by 1996 a virtually bankrupt Lotus had been through three managing directors, including ideally suited ex Ford SVE/Aston Rod Mansfield, and a finance director whose replacement maddeningly sold all the historic Lotus spares and tooling. At least four section directors were summarily sent packing for no obvious reason by Artioli, as was a senior Daewoo director as he suspected he had arrived to buy the company! Then as if by magic, and certainly at the last minute, Tansri Yahaya of Proton (later killed in a helicopter crash) came riding to the rescue installing ex Shell Oil executive Chris Knight as CEO.

Meanwhile the extremely light and advanced extruded aluminium Elise, which was to lead to many copycat chassis, had gained market traction in spite of its aluminium composite brakes and knocking Koni dampers, but again, what of a replacement Esprit?

Cut to the benchmarking exercise with two much lightened Esprits with normally aspirated Lotus V8 engines, plus some competitor cars. At the de-brief there was silence until Knight asked for comment. It was Dave Minter (bless him) who spoke first. “It’s a no brainer – it’s the Esprit”.

We agreed, but Lotus management – as often happened – promptly binned that idea. This was the beginning of a frustrating period. For reasons nobody who mattered could understand, consultants who had never done anything in the auto industry were brought in at upwards of £1,000 a day to tell Lotus designers and engineers that from now on Lotus cars would be produced in the “new way” (shades of Tony Blair) and that it should only take 18 months from first stroke of the pen to production.

And to inspire us all the “Creative Egg” was installed in the main office – an oval plinth with a Classic Team Lotus F1 John Player Special atop. The result? The Alfa-engined M250 concept (with space for golf clubs) was dropped, as was a much later Esprit replacement project, which foundered at a very late stage on several fronts, particularly powertrain supply politics.

Knight left in 2001, to be followed in quick succession by messrs Playle, Kiam and Ogaard-Neilson – all caretakers really. In spite of the apparent lack of direction and technical leadership during this period, one must hand it to Proton (and then DRB Hi-Com) for continuing to invest in Lotus and its facilities. The one bright spot during the 15-year period of Proton/DRB-HiCom ownership was the return of Mike Kimberly in 2006.

Thanks mainly to Kimberley, and Roger Becker’s strong long-term links with Toyota, the underrated Evora (which morphed into a successful GT4 race car) got built, the crosswise V6 powertrain (then supercharged) from a big manufacturer being the only way a business case could be made at all for a new car. Incredibly the whole programme took 27 months from start to finish and cost just £36 million – Lotus at its absolute best.

A worn-out Kimberley cried “enough” and departed once the Evora was in production in 2008. Against the financial meltdown Lotus then faced what was probably the worst three years of all, when a Mr Danny Behar appeared with an expensive briefcase, some overpaid associates, and five totally unattainable projects, plus his excellent references from Red Bull and Ferrari said to exist only to get him employed by somebody else. Arrogance and smoke and mirrors, and a purchased F1 presence prevailed, then suddenly Proton’s rumoured £300+million investment had all but gone….

In spite of desperate times, departing engineering staff, and flaky management, the Lotus brand survives, but what of an Esprit? Funnily enough much of the componentry for a 200mph north/south-engined Esprit was designed into the Evora programme, but as was pointed out, getting it built at the time would seem to dictate a joint venture, with somebody who has an awful lot of cash.