With temperatures like the inside of a deep freezer, guaranteed snow, and enormous ice sheets, winter in northern Sweden offers the perfect conditions for the development team at Audi to tune new models under extreme climate conditions. While great for vehicle development, the closed-off testing grounds in the region are not an easy working environment, as Raphael Kis, an Audi calibration engineer, shares.

The snow crunches under Kis’ shoes on a January morning as he steps into the street in front of his hotel, leaving behind one of the first sets of footprints. The air is crisply cold and the thermometer says -21 degrees (-5.8F). The hum of snowploughs is audible outside the hotel as he and his team push the fresh snow from the frozen lake and prepare the test tracks just a few hundred meters away. Kis has pulled his black woollen cap low over his face and is trudging through the Swedish gloom toward the workshop.

Thankfully the paths are short: “You could say you fall out of the hotel directly into the workshop,” Kis says. It is 07:00 – time to start work for this family man who is responsible for tuning driving characteristics including stability and traction.

The workshop is on the Volkswagen Group’s extensive testing grounds in Swedish Lapland, simply named ‘KALT 1’ for reasons of secrecy. Fences completely seal off the area and everything within is strictly confidential. This is where Audi calibrates its future models on ice and snow surfaces. The testing mecca covers more than 3,600 hectares (8,896 acres) in total – about 1.7 times the surface area of Frankfurt airport. The facility also includes several workshops with office workplaces, a hotel with 440 beds – and, crucially, wintry stretches totalling 83km (51.6 miles) in length.

The next-largest town is several kilometers away and even the nearest supermarket is beyond walking distance. Nonetheless, the roughly 150 employees who are usually on site are well supplied. The all-inclusive package includes three mealtimes in the hotel restaurant, two exercise rooms, and a hotel bar.

“We’re together with a lot of people – you have to like that. If you’re not up for that, you won’t be able to stand it for long” says Kis, who clearly does like the setup as he has been at it for 14 years. He spends about 20 weeks per year at test sites, of which about 10 weeks are spent in Sweden.

Fine tuning in the Swedish winter

On a typical morning, Kis sits in a workshop office and gears up for fine tuning a new Audi model. When his son was younger, he explained his job to him in this way: “Daddy sits in a car and adjusts it so that people can drive safely.”

Admittedly, it is not quite so simple – and Kis dispels one preconception right away: “I don’t drive in circles all day long, as one might imagine,” he says and grins.

For example, new software has to be run on the car and occasionally experts also have to adjust the hardware. Calibrating a vehicle takes over a year, usually one and a half winters: Kis and his colleagues ideally establish a baseline on dry roads in order to adjust the basic handling. Test drives follow on wet road surfaces before the Swedish winter sets in, starting in late November. Ultimately the car should drive harmoniously on dry and wet roads, as well as on ice and snow.

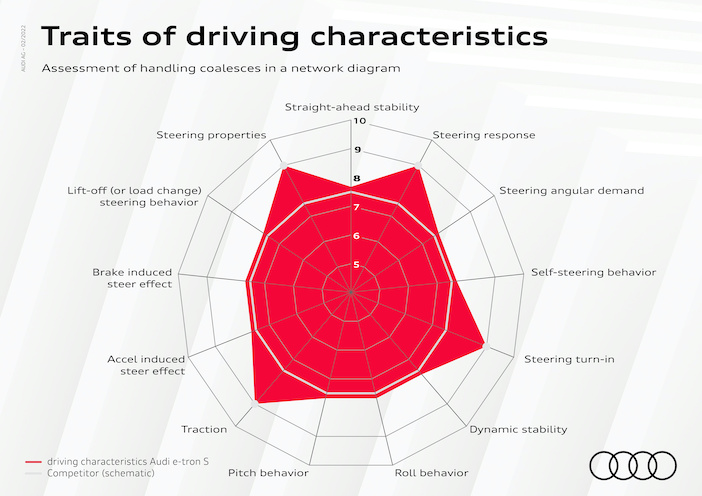

“The ABS, ASC and driving dynamics control have to correspond to Audi DNA,” Kis explains. The automotive group thinks of its DNA as fulfilling certain criteria that characterise an Audi’s handling.

Calibration on dry Spanish roads is on the agenda for February in order to “drive against it”, again in Sweden, as Kis says. “It’s a constant interplay.” A new Audi model’s handling is also refined over the course of a year on mountain roads and passes. “The different road profiles should always be as customer-oriented as possible.” The suspension experts plan on doing the final fine-tuning the following winter.

Adjustments on the laptop

In Kis’s office, thick snowflakes usually flutter from the sky outside the window, illuminated by the light of the workshop. “December and January are the dark months in Sweden – that’s pretty tough,” the developer says.

Some days the sun comes up at 9am and goes down again at 2pm. Kis says that February and March are the most beautiful months in the northern kingdom. That is when the sun and the blue sky occasionally transform the testing grounds into a magical winter landscape. “But you also get used to the darkness. All the roads are well lit by roof-mounted headlights,” Kis says as he wedges his laptop under his arm and grabs the car keys from the desk.

Moments later, the laptop is firmly in its bracket on the passenger seat of a prototype car wrapped in camouflage film. Various parameters can be changed on the computer in order to get incrementally closer to the target characteristics. The Audi should be easy to control – including in the threshold range. All control systems have to respond reliably to the driving conditions that are present. Superior traction is also considered a typical Audi characteristic. Despite the advent of electric cars, tuning has not fundamentally changed over the years.

Driving on thick ice

Kis’ next stop on the testing grounds is a stretch on the frozen lake – about 3km long and created with the same curves each year thanks to saved GPS data. Mounds of snow that were cleared off the route early in the morning are now piled up alongside it. Conifers on the banks groan under the weight of the snow and leave their branches hanging. How will the Audi respond to the icy roadway? Kis presses on the accelerator pedal and the car heads for the first curve to the left.

The Audi drifts through the curve and swirls the snow particles a good 2m up into the icy air. “These are the moments when the job is really fun,” says Kis. The handling specialist routinely steers the car through the course a few times until he has gathered enough information.

He does not need to fear that the sheet of ice will not support the car. At the start of the season, the team checks the ice with a snowmobile and measures its thickness. The ice surface needs to be at least 25 to 30cm (9.8-11.8in) thick for a car to be able to drive on it. If the ice is too thin, hovercraft push the snow off the surface over and over. Given that snow has an isolating effect, the ice would grow more slowly otherwise. The result is a layer of ice that is up to 90cm (35.4in) thick.

Analysing the measurement results

Back in the workshop, after lunch in the hotel restaurant, analysing the measurement results with functional developers and system partners is on the agenda. A certain personal touch is discernible in the calibration, but Kis discusses a model’s target characteristics in advance with the development team leader and other colleagues. The nuances in their opinions vary widely from one to another.

“What happens is that someone thinks that the car should oversteer a little bit more, for example,” says Kis. “But all in all, we have pretty much the same understanding of how the car should drive in the end.”

Darkness has fallen once more over the testing grounds when Kis takes his jacket from the back of the chair and slips on his cap. Quitting time after a 10-hour workday. “Dinner, chatting with my co-workers, and a video call home. Back at it tomorrow!” Kis says and disappears into the light of the hotel lobby.