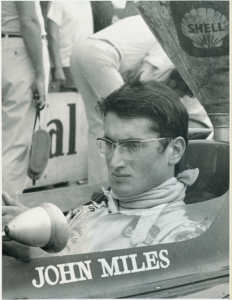

I was racing my Lotus Elan 26R in the GT race at the 1966 Oulton Park Gold Cup. The works Lotus Cortinas were there for Jim Clark and Peter Arundel. As I lay under my car checking something, I felt somebody trying to attract my attention by attacking my ankles. The unsubtle man was Colin Chapman: “John, do you want to drive a Cortina? Jimmy is late for practise.” And so began my relationship with Colin.

I didn’t race the car because Clark turned up 15 minutes into the session, but it didn’t matter – the seeds had been sown, and besides, better was to come: a Formula 3 test session at Goodwood with Jack Oliver. In the end, we both ended up driving new Lotus 47 GTs (the Twin Cam Europa) at the Boxing Day Brands Hatch. I won the race. Colin jumped into the car and said, “Look, I want you to drive for me next year.” All my dreams had come true. So far I had only seen Colin at his magnetic best. I wanted to be a racer and Lotus was the place to be as far as I was concerned. Time, however, was to change my opinion of the man…

Colin seemed to gain more interest in me as the F3 and GT successes came. I got to do more testing, which I loved. Just being around Lotus at that time was exiting. Housed in the brand-new factory at Hethel were Elan and Europa engineering staff, road car production, plus Lotus Components and Team Lotus. My interest in chassis engineering was fostered in this environment; there was always something new going on. This was the time of the then revolutionary stressed Cosworth DFV Lotus 49. In 1968, Colin brought in serious commercial sponsorship with the Players Gold Leaf brand, and even bigger suspension-mounted wings brought dramatic reductions in lap times. In a year or two there would be slick tires. Colin’s cars led these massive advances. But they also broke rather a lot.

Then tragedy at Hockenheim. Early in 1968, Jim Clark was killed in a minor Formula 2 race when his car went out of control due to a slowly deflating rear tire. Clark’s death badly affected Chapman and I didn’t see so much of him for the rest of the year.

More drama early in 1969. Both Jochen Rindt and Graham Hill crashed very badly in their 49s during the Spanish GP when the rear wings folded up in the middle, probably because they had been crudely extended at each end during practise. Jochen and Graham were lucky to escape with their lives. Suspension-mounted wings were banned after the Barcelona incident.

Colin, meanwhile, seeing the dramatic reductions in lap times attributable to four-wheel-drive at Indianapolis, had already decided to run a four-wheel-drive Formula 1 effort, the DFV-powered Lotus 63, in case it proved a better route than 2WD for grip.

This is when I got to know Colin, Graham Hill and Rindt a bit better.I think Rindt had a rather scratchy relationship with Colin. At that time my relationship with Colin was good, if only because I was prepared to do all the testing he wanted on the 63. I also took an avid interest in chassis engineering, which Rindt did not. Colin often used to discuss his concepts over a meal while sketching on a paper napkin. I think if we knew then what we know now about four-wheel-drive systems, the car could have been much better. It was the best of the 4x4s, but it was overweight and suffered from basic handling limitations.

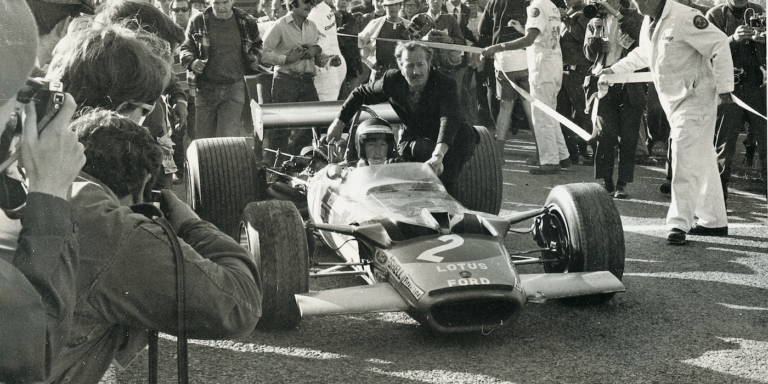

In essence, a normal race car allows the driver to control the front with the steering, and the rear with the throttle. This element of controllability was absent in the 63. Paradoxically, it was good in high-speed corners, where the stability and understeer were an advantage, but ponderous and very understeer-y in the medium/slow bends. The driver had to pick a line and stick to it. Sometimes it even qualified near the middle grid, but it always broke down for me, or stumbled to the finish. Naturally, Colin thought one of the star drivers might do a better job, especially if it was wet. The only decent result was Rindt’s distant second place in a poorly supported Oulton Park Gold Cup. The drivers had been praying all season for rain, but when it eventually did come, at Watkins Glen, it was Mario Andretti who won the fight to drive it. Unfortunately, he was sixth from slowest in the dry and fifth from slowest in the wet.

In essence, a normal race car allows the driver to control the front with the steering, and the rear with the throttle. This element of controllability was absent in the 63. Paradoxically, it was good in high-speed corners, where the stability and understeer were an advantage, but ponderous and very understeer-y in the medium/slow bends. The driver had to pick a line and stick to it. Sometimes it even qualified near the middle grid, but it always broke down for me, or stumbled to the finish. Naturally, Colin thought one of the star drivers might do a better job, especially if it was wet. The only decent result was Rindt’s distant second place in a poorly supported Oulton Park Gold Cup. The drivers had been praying all season for rain, but when it eventually did come, at Watkins Glen, it was Mario Andretti who won the fight to drive it. Unfortunately, he was sixth from slowest in the dry and fifth from slowest in the wet.

Increasing the torque split to the rear did nothing for it except to make it even less controllable in the wet. The fact was that better aerodynamics and tire development had rendered a 4×4 F1 car pointless.

In the US Grand Prix, Graham Hill broke both his legs in a massive accident due to a rear puncture. Shortly after, the call came from team manager Andrew Ferguson. It was uncertain if Graham would be fit, even for the following season. Jochen hated testing, so would I like to do some more testing for the F1 team and possibly drive the revolutionary Lotus 72 with Rindt the following year? My fee? A £1,000 retainer, £350 per race and a small percentage of any prize money, but I had to pay my own expenses! I once asked Colin for some money because I was absolutely broke. He pulled out his wad and peeled off £300. He was a man of extremes. He had an eye for elegant, lightweight (if fragile) engineering solutions, yet was unable to understand the appeal of antique furniture when you could make a reproduction, using modern materials and glues, that would be almost indestructible. I don’t know anybody who could digest information faster, time a full grid on one split-hand watch, or make decisions quicker. Nor do I know of any Formula 1 team where the mechanics often had to work until they dropped – literally – but they did it gladly for Chapman.

No season saw such highs and lows as 1970, which started with the disastrous debut of the wedge-shaped 72, and ended with Rindt becoming a posthumous world champion, my dismissal, and Emerson Fittipaldi winning the US Grand Prix.

After coming fifth in South Africa driving a 49 I was feeling quite chipper. We all looked forward to the 72: mid radiators, inboard front brakes, torsion bar suspension et al. Initially, it was a disaster because of the dramatic amount of anti-dive and anti-squat applied to the suspension; it would ‘lock up’ if you were braking or accelerating. Once these characteristics were removed and the front brake heat dissipation problems sorted out, Jochen’s car started to fly. Mine was somewhat behind in the mods and usually broke. I could sense that Chapman was losing faith in me. He gave me a rocket at Hockenheim for nearly missing practise after the plane broke down at Heathrow. At Spa, Jochen drove a 49 and cautioned me about driving the 72 after a wheel fell off at la Source. At Zandvoort he spun and bent the monocoque without hitting anything. There were other failures, but Jochen’s car did hold together for him to win several GPs. He also had an amazing win at Monaco in a 49 and suddenly he was leading the championship. For me, the final confidence breaker was when a front brake shaft snapped, nearly sending me into the trees at the Austrian GP.

What was going to fall off next? Deep down my tolerance level for breakages was being tested to the limit. There was an air of unreality at Monza when Colin decided to run three 72s, the third for Emerson. The cars arrived late because the mechanics had been working all- nighters to get the cars completed. The arguments will continue as to what made Jochen turn sharp left into the barrier at the end of the straight and die from his injuries. He was dashing to clinch the championship. It was he who asked for the wings to be removed. His car looked dreadful in the corners, but with suitable gearing it would attain more than 320km/h (200mph) on the straight.

Seeing this, Colin insisted I remove the wings on my car. One lap was enough to convince me that my car was undriveable. It snapped into oversteer at the slightest provocation. Colin then ordered me to take the wings off my car for the final day of qualifying. I argued, but to no avail. Jochen died in the first few minutes of qualifying the following morning. Thankfully I never got out. The violence of his departure from the straight still inclines me to think that a brake shaft broke. We shall never know for sure, but it was upsetting to discover a rumour put about that Colin had warned Jochen about driving the car without wings because I had said it was so unstable… volte-face.

Of course, it was the last GP I attended for Lotus. Chapman didn’t dismiss me, but left it to new team manager Peter Warr. Several years later, long after I had finished racing, I saw Colin at a motor show. His hair had turned pure white. The twin chassis 88 had just been outlawed again (very sad), and the Delorean affair was about to break. We chatted and passed on. The old Chapman magic seemed to have gone – or perhaps I had just grown up.