In an age when dozens of engineers are employed to develop a single new chassis, it’s remarkable to think there was once a time when individuals were responsible not only for the whole dynamic package, but the design of an entire vehicle.

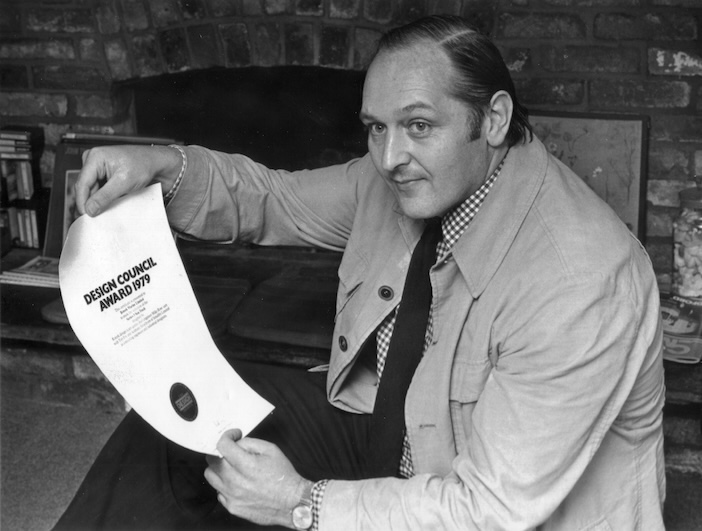

Tim Fry (25 August 1935 – 17 May 2004) was from this breed of talented all-rounders. On leaving school in 1953, he joined Humber, part of the Rootes Group of car companies, as an apprentice engineer. Already responsible for a styling facelift on the Sunbeam Rapier, at age 20 he embarked on designing and engineering the car for which he’s best remembered – the Hillman Imp.

The Imp started life when Fry met another young engineer at Rootes, Mike Parkes. Both were keen drivers – Parkes would later race works Ferraris – and as such deemed Rootes’ product range “boring”. In 1955 they set about persuading management that something more fun to drive was required, securing approval to explore the feasibility of a 60mph, 60mpg small family car, partly in response to the fuel shortage caused by the Suez Crisis in 1956.

The first prototype, known as the Slug because of its dumpy looks, was inspired by the Goggomobil microcar. Like that car, it was rear-engined for cost and packaging reasons, with swing axles front and rear for lively handling. It also incorporated innovative 10in wheel rims, which bolted directly onto the brake drums to improve cooling and save weight.

The rims didn’t make it to the production stage, but when the Imp finally emerged in 1963 it retained the Slug’s basic configuration. As a rear-engined, rear-drive design it was the complete opposite of its more famous rival, the Mini, but had stronger brakes and a smaller turning circle than the BMC machine. Fry and Parkes were friends of Mini designer Sir Alec Issigonis and its suspension guru, Alex Moulton.

In his final interview, Fry recalled that when Issigonis tried an Imp for size, he said it was “brilliant, but you’ve got it the wrong way round!” The debate didn’t end there: “I was having a good-natured argument with Issigonis,” Fry remembered, “and he said, “a front wheel drive car is like a dart, it’s very stable”. I said, “Yes, but darts don’t go round corners.” I don’t think we got any further than that…”

Fry was typically forthright – and more than a little stubborn – in his advocacy of rear-wheel drive. In 1975, he authored an article in the New Scientist titled ‘Rethinking the design – logic versus fashion’. In his own words, the piece “proved conclusively that front-wheel drive is a waste of time”, pointing out that “Mitsubishi produces a perfectly reasonable front-engine/rear-drive car six inches shorter than a Mini”. The piece provoked a number of critical responses from advocates of front-wheel drive, but Fry was unmoved; looking back on it nearly 30 years later, he concluded that he “wouldn’t change a word of it”, and was looking forward to driving the 1-Series.

The Imp remained in production at the Linwood factory in Scotland until 1976, but Fry parted company with Rootes in 1970. Chrysler was by now in charge, and after working on the Avenger, 180 and stillborn MPV and sports car concepts, as well as completing a secondment to Detroit, Fry tired of big-company politics and went freelance.

As a director of design consultancy Smallfry, he penned everything from ferries to hairbrushes, but continued to work on road transport projects such as the Fry Dependent Suspension. This design was a patented hydraulically connected terrain-averaging suspension for an unsprung vehicle, incorporated onto Aveling Barford road graders. In 1977, Smallfry was commissioned by Volkswagen to design a GRP-bodied, Beetle-based estate car and pick-up for South Africa; they were approved by Wolfsburg, but the decision was taken to sell the Golf there instead. Other work centred on reducing the rollover risk of, and road damage caused by, articulated heavy goods vehicles.

At the other end of the scale – and true to the concept of the Slug – Fry remained concerned about vehicle weight. His interest was from both a dynamics standpoint and because, as he said, “in ecological terms it’s the one factor that makes most difference”.

In 1981 he completed a feasibility study into an ultralight commuter car for Sir Clive Sinclair, which had similar first principles to the Smart Fortwo: “economical, appearance very important, smaller than the smallest ‘real’ car”.

Fortwo was also the car Fry used for comparison when driving an Imp for its 40th anniversary in 2003: “The Smart has two or three miles an hour on top speed over the standard Imp, but it’s got about the same overall fuel consumption, the same turning circle, and it’s 70kg heavier,” he reasoned. “I expected the Imp to feel old-fashioned, but the overall impression was how easy it was to drive, and how well you could see out of it. I’m quite big but there’s plenty of room. Why do we need such big cars nowadays?”

Over 20 years on from that anniversary, what would Fry make of the size of cars in 2025?